A ride to the tip of Newfoundland’s Northern Peninsula reveals North America’s first Viking village

The ferry slid smoothly into Channel-Port aux Basques, Newfoundland, at 4:30 a.m. In the rain and pre-dawn darkness, I was able to follow a line of cars, knowing I was already breaking the first rule of riding on the Rock: don’t ride at night. A road sign even announced “Number of vehicle–moose accidents this year: 606.” I certainly didn’t want to force some Ministry of Transportation worker to have to change the sign to 607, and without the cautious procession leading the way, I would have holed up at the dock and waited for daylight. As it was, however, the sky was brightening by Stephenville, and the rain stopped by Corner Brook. Even in the dark, I had been aware of the impressive mountains to my right – the Long Range and then the Annieopsquotch Mountains – and to my left I caught glimpses of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Just out of Corner Brook, daylight revealed beautiful Marble Mountain and my first taste of the scenery that I would be riding into.

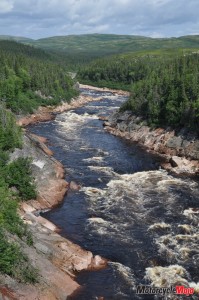

At Deer Lake, I pointed my new Honda NC700X’s front wheel northwest onto Highway 430: The Viking Trail. This led me first into Gros Morne National Park, and then up the western shore of the Northern Peninsula. Spectacular views, one after another, presented themselves to me. Further north, fishing villages such as Hawke’s Bay, Eddie’s Cove, and Plum Point give a window into the hard-won livelihoods of many Newfoundland families – lobster traps stacked beside moored fishing boats, simple homes and gardens randomly appearing far from anywhere – all dot the sides of the highway, as do stacks of cut firewood.

At Deer Lake, I pointed my new Honda NC700X’s front wheel northwest onto Highway 430: The Viking Trail. This led me first into Gros Morne National Park, and then up the western shore of the Northern Peninsula. Spectacular views, one after another, presented themselves to me. Further north, fishing villages such as Hawke’s Bay, Eddie’s Cove, and Plum Point give a window into the hard-won livelihoods of many Newfoundland families – lobster traps stacked beside moored fishing boats, simple homes and gardens randomly appearing far from anywhere – all dot the sides of the highway, as do stacks of cut firewood.

At the end of the road, I stopped at Viking RV Campground in Quirpon (pronounced car-poon). They offered simple accommodation by way of a wooden, yurt-style base for my tent. In the morning, I enjoyed my introduction to bakeapple and partridgeberry jams. Grace, the owner and cook, picks these ubiquitous berries to make the jams that complement her homemade breads.

The day was cool and breezy, which may not be perfect conditions for riding, but here it is actually preferable, as it keeps the incessant black flies and mosquitoes at bay. Because the land is largely Precambrian rock, with little soil left by the scouring glaciers, the frequent rains create thousands of pools – perfect breeding grounds for those predatory pests.

I rode out to L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site, the only known Viking settlement in North America and the earliest evidence of Europeans in the western hemisphere. It was roughly one thousand years ago that a Norse expedition made its way from Greenland to this strategic location on the rocky Newfoundland coast. Here, Leif Erikson led 60 to 90 hardy explorers to set up a camp with turf-walled buildings, to be used as a wintering base for exploration further south in search of hardwood lumber. Discovery of wild grapes led to the naming of Vinland, and also to the bad news that these grapes were not free for the taking, but were claimed by aboriginals who had already been here for thousands of years. The Vikings were not known for their skills in diplomatic conflict resolution, and friendly trading soon turned to combat. A decade or two later, when the Vikings abandoned this site as a non-viable enterprise, the natives shed not a tear.

I rode out to L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site, the only known Viking settlement in North America and the earliest evidence of Europeans in the western hemisphere. It was roughly one thousand years ago that a Norse expedition made its way from Greenland to this strategic location on the rocky Newfoundland coast. Here, Leif Erikson led 60 to 90 hardy explorers to set up a camp with turf-walled buildings, to be used as a wintering base for exploration further south in search of hardwood lumber. Discovery of wild grapes led to the naming of Vinland, and also to the bad news that these grapes were not free for the taking, but were claimed by aboriginals who had already been here for thousands of years. The Vikings were not known for their skills in diplomatic conflict resolution, and friendly trading soon turned to combat. A decade or two later, when the Vikings abandoned this site as a non-viable enterprise, the natives shed not a tear.

Fast-forward to 1960, when Norwegian explorer Helge Ingstad came upon a site the locals called “the old Indian camp.” It turned out to be a lot more. The foundations of Viking halls and forges, along with iron nails, bone fragments and stone weapons, lay beneath a thin layer of soil and lichen. Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the settlement has been recreated as it was in that mythic and exciting time. For a moment, I thought I had landed on the set for Hobbiton in Lord of the Rings. Several halls made of sod, with walls six feet thick and lined with wood panelling, stand inside a cobbled fence. Actors in period dress keep the fire lit and practice Viking crafts, such as spinning sheep’s wool into yarn for weaving, carving tools and weapons, and forging iron.

I took a cue from two other riders I met in St. Anthony and rode north to Burnt Cape Ecological Reserve in Raleigh. I’m glad I decided on the NC700X, as opposed to the S, because of its higher ground clearance that helped with the loose gravel and shale in this area. These vast limestone barrens are home to over 300 species of plant, including 30 rare species, and one that is not known to exist anywhere else in the world. So bare is the landscape that it seems otherworldly, the strange, tiny plants clinging tenaciously to the rock.

I took a cue from two other riders I met in St. Anthony and rode north to Burnt Cape Ecological Reserve in Raleigh. I’m glad I decided on the NC700X, as opposed to the S, because of its higher ground clearance that helped with the loose gravel and shale in this area. These vast limestone barrens are home to over 300 species of plant, including 30 rare species, and one that is not known to exist anywhere else in the world. So bare is the landscape that it seems otherworldly, the strange, tiny plants clinging tenaciously to the rock.

I finished the day with a tour of Raleigh’s Working Fishing Village, a village that has been preserved as it was in the 1950s, well before the 1992 Cod Moratorium. The remaining 150 residents have sought out ways to rejuvenate the town by creating a living museum. The town invites visitors to stay, learn to haul a cod trap, and take lessons in traditional quilting, rug-hooking and paddle-making.

I returned south to St. Barbe, on the peninsula’s western coast, where I set up camp and waited for the morning ferry to the mainland.

Six o’clock came early, but I was up and eager to explore the place Leif Erikson called The Markland. It was a 90-minute cruise across the Strait of Belle Isle. Docking at Blanc-Sablon, just inside the Quebec border, I rode north on the only paved highway on the coast. Much of this untouched land remains as it has been since the last ice age. Crossing into Labrador, I stopped in L’Anse Amour, population: 9. Meaning “Cove of Love,” its name has been romanticized from the original L’Anse aux Morts, or “Cove of the Dead,” so named for its many shipwrecks. Riding further along the dirt and lightly muddied road to Point Amour brought me first to the wreck of the HMS Raleigh, which ran aground in these waters on August 8, 1922. The 700-crew British warship was steaming at top speed from Newfoundland toward Forteau Bay, where officers were eager to do some salmon fishing.

Thick fog obscured their route, and while narrowly avoiding a collision with a massive iceberg, the Raleigh veered into shallow waters, the rocks of the bay ripping a 360-foot gash in her belly, just 200 yards from shore. The rusting remains litter the shore of Point Amour, while large signs warn of the possibility of unexploded live naval shells in the area. I stepped lightly. Less than a kilometre up the shore, I stopped again, this time to tour the Point Amour Lighthouse. This working light station was built in 1854 and is the tallest light on the Atlantic seaboard. The lightkeeper at the time helped save all but 11 men, who perished on the HMS Raleigh. Just off shore, I watched as gannets began to dive-bomb the sea, so many at once that it looked like a machine gun firing into the swirling salt water. Likely there was a humpback or minke whale, I was told. The gannets reap the benefits of the whale’s search for food. They hit the water at 100 km/h, pushing their prey deep under the water and capturing them on the way back to the surface. It was an amazing display.

All the pavement I’ve ridden on so far has been in very good condition, but today my journey ended where the pavement did, at Red Bay. This village of 211 residents, already a National Historic Site, was recently granted status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in June 2013, as it is the most complete example known of the first industrial-scale whaling activities in the world. Attracted by the large population of whales that moved through the Strait of Belle Isle, Basques whalers established a thriving whale oil industry at numerous ports in southern Labrador.

By 1540, Red Bay was the largest and busiest. Archaeological work has led to the discovery of four sixteenth-century galleons at the bottom of the harbour. One of these was the San Juan, a vessel that had been recorded as “missing” until now. Due to the cold climate, it is the best-preserved shipwreck of its time, revealing information not previously known. Too soon, I had to travel back to Blanc-Sablon and the return ferry to St. Barbe, where I camped for the night. This was my first lengthy trip on my new Honda NC700X, which had drawn my attention by reports of 3.25 L/100 km, although when travelling any distance at speeds, shall we say, more invigorating than the posted limit, efficiency dropped noticeably.

It can be quite a distance between gas stops in rural Newfoundland and Labrador, but I was confident that the NC would serve me well between fill-ups. In spite of my love of riding, let me say that unless you are describing a summer beverage, the adjectives cold and wet do not belong together. My morning ride to St. Anthony was a little less enjoyable than most. When I finally arrived at Lightkeeper’s Seafood Restaurant on Fishing Point, I was so cold and cramped – my hands and limbs barely responding – that I rolled to a stop in the parking lot and promptly fell over. The scratches on the pannier of my bike were injury enough, but to topple in front of the restaurant’s large picture windows left bruises on my ego.

A bowl of hot chowder warmed my bones, and the bakeapple cheesecake made everything better. Fishing Point in St. Anthony is not to be missed. A number of hiking trails explore the area, including Iceberg Alley and Whale Watchers Trail. Whales are regular – almost daily – visitors, in season, and icebergs are frequent. In fact, were it not for the fog, my waitress told me as she pointed to the window, I would see a large iceberg right there!

I rode until dusk and made my way south on 430 as far as Brook Pond, just north of Daniel’s Harbour. The NC is a fine bike, but the addition of a 5 cm Wunderlich screen extender to stop buffeting and a Butt Buffer seat pad, which upped my maximum riding time considerably, made it all that much better. At Brook Pond, I found a grassy track that led me toward the shore and behind a stand of balsam fir trees. It was a beautiful spot to set up camp, overlooking the ocean in the falling dark. Not until the light of day did I discover that I had camped in the middle of a caribou slaughtering ground. Bleached bones lay everywhere around me, including a head still covered with fur and rotting meat.

Passing through Daniel’s Harbour, the skies opened up again, and I rode through driving rain toward Western Brook Pond. I had booked a boat tour of the famous inland fjord, and I really hoped the weather would not disappoint. As if on cue, as I pulled into the parking lot, the clouds broke and warm sunshine poured down. Western Brook Pond was one of the key reasons Gros Morne National Park was established in 1973. At 1805 square kilometres, the park is the second largest national park in the province (only Labrador’s Torngat Mountains National Park is larger). Western Brook Pond boasts the highest cliffs in North America at 610 metres and offers breathtaking, iconic views of what was once a proper fjord before the glaciers retreated and the bedrock rebounded, leaving the pond landlocked.

The salt water was eventually flushed out, and the lake, little affected by human activity, is now one of the purest bodies of fresh water in the world. My final stop was at Tablelands, another reason for the park’s existence. Also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, this 20-kilometre, orange-coloured mountain is made of peridotite. Its uniqueness stems from the fact that it’s a giant piece of the earth’s mantle, thrust out of the ground from 35 kilometres beneath the surface by the collision of tectonic plates some 300 million years ago. Along with the various heavy metals that make the rock toxic to plant life, iron in the rock rusts when exposed to the air, thus causing the unusual colour. It’s strange to see this barren, rust-coloured mountain, facing the thick green forests of the Lookout Hills directly across the highway. As I turned toward home, I began to reflect. The entire Northern Peninsula is a dream location for geologists, archaeologists and historians. And the scenery elicits gasps at every turn. Leif Erikson really had no idea what he had accomplished or what a wonder he had found. Newfoundland and Labrador may largely be simple Precambrian rock, but it is a gem on the Canadian landscape that I will certainly want to visit again.