Born of a passion for performance that continues to this day

Ducati is the only motorcycle manufacturer to ever produce and sell street bikes powered by desmodromic engines. Such engines were originally built strictly for Grand Prix-class road racing, of both the two- and four-wheeled variety. Desmodromic engines differ from other 4-strokes in that rather than the valves being closed by valve springs, they’re closed directly by a mechanical method, such as a rocker or pushrod. Mercedes won back-to-back Formula One World Championships in 1954-55 with its W196 straight-8 desmo GP race car, driven by Argentinian legend Juan Manuel Fangio. This achievement captured the imagination of a young up-and-coming motorcycle engineer by the name of Fabio Taglioni – the future father of the Ducati Desmo and the man the world would come to know as Dr. T.

Brothers Bruno, Adriano and Marcello, along with their father Antonio Cavalieri Ducati, established their company in 1926. Over the next two decades, the Ducati family built the company into a successful manufacturer of vacuum tubes, electronics and a host of other radio components. It wasn’t until 1946, and the end of the Second World War, that Ducati began producing motorcycles.

An Eye For The Future

During the years immediately after the war, a large and growing market emerged throughout Europe for simple, affordable and low-maintenance mopeds, motorcycles and scooters. Ducati saw a new business opportunity and began building Cucciolo mopeds, which consisted of a simple 48 cc pushrod, single-cylinder engine fitted into a bicycle-type frame. Over the next six or so years, the company continued its electronics production in addition to building a range of Cucciolo variations along with other simple, sub-100 cc motorcycles.

During the years immediately after the war, a large and growing market emerged throughout Europe for simple, affordable and low-maintenance mopeds, motorcycles and scooters. Ducati saw a new business opportunity and began building Cucciolo mopeds, which consisted of a simple 48 cc pushrod, single-cylinder engine fitted into a bicycle-type frame. Over the next six or so years, the company continued its electronics production in addition to building a range of Cucciolo variations along with other simple, sub-100 cc motorcycles.

By 1953, the decision was made to split Ducati into two separate businesses, one of which (Ducati Elettrotecnica) produced electrical products, while the other (Ducati Meccanica SpA) manufactured motorcycles. Giuseppi Montano would head up the motorcycle operation and establish road racing as a core activity – a focus for Ducati that persists to this very day. Montano believed road racing was a way to both demonstrate the technical prowess of the young firm and quickly enhance its brand recognition.

To achieve this, Montano needed a chief designer with GP experience who could conceive and create both the road racing and street machines that would fulfill his vision. In 1954, he hired Fabio Taglioni, who had previously designed racing engines for FB-Mondial, as its chief designer. Ducati’s new division received the necessary funding and support required to establish an effective competition department and factory works racing program.

Within two years, Taglioni had built his first desmo GP bike: a 125 single that won its first ever race, the Swedish Grand Prix, in the hands of works rider Gianni Degli Antoni. During the race, Antoni and his Ducati lapped the entire field on his way to the checkered flag.

By 1958, Ducati was committed to a full works GP race program and fielded a team of six riders to get the job done. Had it not been for a crash while leading the Ulster GP by Ducati works rider Alberto Gandossi, the company could have won its first World Championship. As it was, Gandossi was runner-up in the FIM 125 Series to MV Agusta works rider Carlo Ubbiali, with the other Ducati works riders finishing third, fifth, sixth, eighth and tenth overall. Ducati finished the 1958 season at Monza, where it thrashed MV, taking the first five places in front of the home GP crowd.

Expanding The Brand

After the 1958 GP season, with its brand having gained considerable recognition, Ducati turned its energies to improving and expanding its line of street bikes. Taglioni developed a standard SOHC single-cylinder engine design for a growing line of 125, 160, 175, 200, 250 and 350 cc machines, which included touring, scrambler and sport models. By the mid-1960s, Ducati was well established as a volume producer of small- and mid-displacement motorcycles.

After the 1958 GP season, with its brand having gained considerable recognition, Ducati turned its energies to improving and expanding its line of street bikes. Taglioni developed a standard SOHC single-cylinder engine design for a growing line of 125, 160, 175, 200, 250 and 350 cc machines, which included touring, scrambler and sport models. By the mid-1960s, Ducati was well established as a volume producer of small- and mid-displacement motorcycles.

In 1966, Ducati’s largest model was the 350 Sebring, a 340 cc touring bike that was good for about 129 km/h in stock form. The manufacturer’s fastest street bikes were the 250 cc Mach 1 (sold in Canada) and the 250 Mark 3 (sold in the U.S.A.), both of which could exceed 161 km/h (100 mph, or the so-called Ton) in fifth gear, and for a while shared the title of world’s fastest 250 cc street bike.

Both 250 sport models were little more than thinly disguised Clubmans racers fitted with a headlight, brake light and street muffler. Not especially comfortable or practical for around-town riding, these bikes were happiest at speed, and reacted poorly to being lugged (ridden slowly with engine revs below 3000 rpm).

Taglioni had always nursed a dream of building desmos for the street. By 1967, he was also mindful that his earlier, so-called narrow-case engine designs had gradually revealed areas where significant improvement was both possible and increasingly necessary in light of the growing middle-weight competition from Japan.

Taglioni’s later 1950s desmo racing engines had used complex double and triple overhead cams driven by bevel gears and shafts coming off the crankshaft, systems that enabled the little engines to rev to 14,000 rpm. These were both too costly, far too complex and, in reality, inappropriate for use on the street bikes of the day. Taglioni needed a simpler and more cost-effective design.

A New Approach

Desmo engines were originally developed to eliminate the problem of “valve float,” not uncommon to 4-stroke engines in the 1950s, ’60s and early ’70s. Valve float occurs when valve springs prove incapable of closing valves fast enough to get out of the way of a rapidly rising piston. This can happen if the springs get tired, or if an engine is revved beyond its red line, with the result being the piston strikes the valve before it’s seated; bent or broken valves often caused catastrophic engine damage. Desmo engines totally eliminate the risk of valve float.

Desmo engines were originally developed to eliminate the problem of “valve float,” not uncommon to 4-stroke engines in the 1950s, ’60s and early ’70s. Valve float occurs when valve springs prove incapable of closing valves fast enough to get out of the way of a rapidly rising piston. This can happen if the springs get tired, or if an engine is revved beyond its red line, with the result being the piston strikes the valve before it’s seated; bent or broken valves often caused catastrophic engine damage. Desmo engines totally eliminate the risk of valve float.

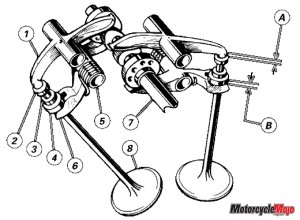

Taglioni came up with an ingenious desmo system that could be integrated into his basic SOHC design with minimal changes. It incorporated two rockers: one upper and one lower, for each valve. The upper rocker pressed against the end of a valve to push it open; the lower rocker had a split opening at the end, forming two fingers between which the valve stem travelled. The desmo valve design incorporated a type of metal collar or ring, which the closing rocker lifted, pushing the valve toward its seated, or closed position, in the cylinder head.

In Taglioni’s design, the single overhead desmo camshaft had four large cam lobes, each of which caused…