Travel by motorcycle through Canada’s Rockies provides some of the world’s most breathtaking scenery.

In a quest partly for adventure and partly to wring the greatest number of travel miles from my paycheque, I have begun what I call vagabonding. That is, rather than making reservations in a hotel or campground, I simply stop at places along my route that look reasonably safe and comfortable when I am tired, cover the bike, and roll up in a tarp for the night.

Carrying the minimum of necessaries, I recently set out from St. Catharines, Ontario, with my destination being the western tip of the Trans-Canada highway in British Columbia. Eventually. At my very first stop for fluids (for both me and the bike), the rear tire picked up a metal shard that triggered a lot of hissing (from both me and the bike). Unloading the saddlebag to retrieve the repair kit, I plugged the puncture and was again en route, wondering just how long this patch job would last, as it was Sunday and I was not likely to find a shop that could otherwise help me. I continued – on a plug and a prayer (all the way to Vancouver, as I was pleased to learn).

After four days and 3700 kilometres of vagabonding – and a cloud of black flies near Kenora – I arrived in Banff, Alberta, dirty, exhausted, my windscreen opaque with bug splatter. Fortunately, a hostel is a great value if you are travelling alone and enjoy meeting other travellers, and most run about $40 or less. A hot shower and a soft bed rapidly gained priority on my list of crucial commodities.

Just as summer brings Canadians out of their winter burrows and neighbours become more social, so does stepping out of a cage to ride a bike. At gas stations, restaurants and various attractions, people strike up conversations simply because you are on a motorcycle. On this trip, I met some of the most interesting and adventurous people in just this way, such as the rider who was on his way from Dead Horse, Alaska, to his home in Washington, D.C. – by way of Yellowstone, Denver and Duluth – or the young woman on her Honda Valkyrie travelling solo from Seattle to Anchorage.

Just as summer brings Canadians out of their winter burrows and neighbours become more social, so does stepping out of a cage to ride a bike. At gas stations, restaurants and various attractions, people strike up conversations simply because you are on a motorcycle. On this trip, I met some of the most interesting and adventurous people in just this way, such as the rider who was on his way from Dead Horse, Alaska, to his home in Washington, D.C. – by way of Yellowstone, Denver and Duluth – or the young woman on her Honda Valkyrie travelling solo from Seattle to Anchorage.

Canada’s Rockies are high points in every sense, and well worth the travel time from anywhere in the world. Banff is one of Canada’s authentic gems, first settled when the Canadian Pacific Railway was built through the Bow River Valley in the 1880s. Rail workers discovered hot springs on the side of Sulphur Mountain, and the Canadian government began promoting the area as a resort and spa in order to support the construction of the transcontinental railway. In a further effort to attract wealthy travellers, the Canadian Pacific built a series of grand hotels along the rail line, including the Château Frontenac in Quebec City and the Banff Springs Hotel. Even now, the opulence of these hotels is remarkable. The main view from the Banff Springs Hotel looks across the spectacular Bow River Valley and toward Mount Rundle, which is frequently cited in geology books because of the ancient seabeds exposed near its peak.

The chaotic power of this mountain-building activity must have been amazing – and terrifying! One can only survey these timeless mountains with a kind of reverence and humility. Main Street, Banff, is adorned with a spectacular view of Cascade Mountain. The Bow River itself is one of many sparkling, tumbling rivers, clearer than I ever expected. Appropriately, in 1984, the UN declared Banff National Park a World Heritage Site.

The Bow Valley Parkway (Hwy 1A), lined with daisies, stands of white birch, pine and aspen, and presided over by majestic peaks, runs parallel to the Trans-Canada from Banff to Lake Louise. From there, the Icefields Parkway (Hwy 93), one of the world’s most picturesque routes, leads north to Jasper. Anywhere else, I would say the day began with spitting rain, but here, it seemed more like a christening.

The Bow Valley Parkway (Hwy 1A), lined with daisies, stands of white birch, pine and aspen, and presided over by majestic peaks, runs parallel to the Trans-Canada from Banff to Lake Louise. From there, the Icefields Parkway (Hwy 93), one of the world’s most picturesque routes, leads north to Jasper. Anywhere else, I would say the day began with spitting rain, but here, it seemed more like a christening.

My first stop was Lake Louise, which was created from glacial meltwater. As the glacier creeps along, it grinds stone into “rock flour,” giving the water its resplendent turquoise colour. After enjoying a twisty, 14-kilometre ride to Moraine Lake, I encountered my first sign that grizzlies were nearby, in the form of an actual sign that read: “Group access is mandatory beyond this point. Travel in a tight group of 4 or more for safety. Failure to comply could result in a $5,000 fine.” Apparently, the probability of alarming a 700-pound omnivore with shredding claws and tearing teeth isn’t deterrent enough for some people. As for me, the bears were welcome to their peace and quiet in the Valley of the Ten Peaks. I turned my attention to the magnificent Moraine Lake, one of the most photographed locations in all of Canada, featured on the backside of our $20 bill from 1969 to 1979. It is hard to imagine anyone could take a bad photo of this place.

Just north, I left the Trans-Canada and followed the Icefields Parkway, bordered by the bright red of Indian paintbrush and frequented by black-billed magpies. Crossing the North Saskatchewan River, I looked back to take in the vista from understatedly named “Big Hill Viewpoint.” The rounded Saskatchewan River Valley sweeping between Cirrus Mountain, Mount Saskatchewan and the Weeping Wall, dwarfed human, vehicle and even the ribbon of highway below. I rode on toward the Athabasca Glacier, where again, humans were imperceptible flecks on one finger of the Columbia Icefields.

Because of a warming climate, the Athabasca Glacier has been melting for the last 125 years. Markers illustrate how it has receded more than three kilometres, almost one kilometre of that in just the last decade. Earlier in the day, I had seen how the Crowfoot Glacier had lost most of its third “toe” to global warming as well – graphic images of an inconvenient but almost certain truth. From here, I followed the Athabasca River, not to its terminus in the Arctic Ocean, but as far north as Jasper, where the renewed possibility of grizzlies prompted me to forego the vagabonding in favour of a hostel. First, however, I stopped to marvel at the powerful Athabasca Falls, and to watch rafters on the river just below Jasper. I spent a fascinating evening sitting by a fire and meeting travellers from Switzerland, Austria, Holland and Australia. The Aussie was a stonemason who had just canoed from Whitehorse to Jasper, and before that had been canoeing in Alaska. By comparison, my adventure seemed tame. The next morning, on my way back down Highway 93, it was so cold that I put on almost everything I had in my saddlebags, including newly purchased long johns and T-shirt, and was still cold! I held my coffee in my hands a long time, just to bring the feeling back to my fingers. Approaching the border to British Columbia, the sun was searing down and I had to pull off the extra layers.

But by Kicking Horse Pass, I was being christened yet again, with an all-out water baptism just beyond Rogers Pass. This didn’t prevent me from admiring the railway tunnels that spiral in and out of the mountain face – a solution for a dangerously steep grade that had previously been the cause of several train wrecks and a few deaths. The construction of the tunnels themselves cost an average of one death per week among the mostly immigrant workers. By today’s norms, the 10-hour days and lack of safety standards, all for less than $2 a day, seem inconceivable. I paused at Craigellachie, where the last spike of the CP Railway was driven in 1885, a spike that would open the country to travel and trade, and solidify us as a nation.

I detoured to Takakkaw Falls, one of the highest in Canada at 254 metres. Takakkaw is Cree for “it is magnificent,” and it truly is. I imagined native people standing on this very spot thousands of years ago and sharing my awe and admiration. Rogers Pass, a high point at 1330 metres, includes a series of tunnels, most only partially buried, which appear to function more as protection from rock falls and avalanches than as tunnels through the mountain. In Salmon Arm, I found a spot to sleep in a secluded meadow along the shore of Shuswap Lake. It was perfect – until a scheduled, mile-long CP train thundered through at 3:00 a.m. not a hundred feet from my head! While having breakfast at a Tim Hortons, I listened as three older men, two of whom used to work for the railroad, described their work. “Some of these trains are so long now,” said one, “you have to start slowing down by Chilliwack if you want to be able to stop for a crossing in Abbotsford. And you get in the canyon . . . if you have a problem and have to get out to look after it, you can be gone two hours walking to the back of the train over rocks and rubble.”

Just outside of town, I spied an osprey and her mate building a nest atop a hydro pole over the highway. The ospreys were a marvel to watch, as was the bald eagle that accompanied me for some distance before considerately posing in a tree for a photo. The landscape around Kamloops consisted of massive but rounded hills, which met the water at Kamloops Lake and provided just enough room along the far shore for the seemingly toy train to speed along. This is very dry country, as the Pacific westerly winds drive moisture up the mountains, dropping much rain along the coast, and then, thirsty and parched, enter the Thompson and Fraser Valleys. You can see remnants of clouds being pushed over the peaks, promising rain but seldom delivering; only irrigation allows farming here. Fortunately, the rivers are full and mighty. The Thompson and Fraser meet at Lytton and then force twice the water of Niagara Falls through a particularly narrow opening between sheer canyon walls.

In 1808, explorer Simon Fraser wrote in his journal that he had just navigated “a place where no human should venture, for surely these are the gates of Hell.” And the name stuck: Hell’s Gate. Things became remarkably greener from Hope to Vancouver – and remarkably more congested. It was stop and go from Chilliwack through to Vancouver, but I finally found my way to the beautiful hostel at Jericho Beach. Up early to catch the ferry to Vancouver Island the next morning, I discovered that my rear tire had worn down enough that the plug was no longer holding air. A revised plan included an appointment for a tire and oil change, while I toured the city, visited Chinatown, stopped at Canada Place for a photo by the 2010 Winter Olympics Cauldron, and relaxed. I then explored Gastown, the former heart of the city that later deteriorated into Vancouver’s Skid Row, though it has more recently undergone gentrification as the city’s trendy tourist district. Then it was off to Stanley Park, once home to several First Nations tribes.

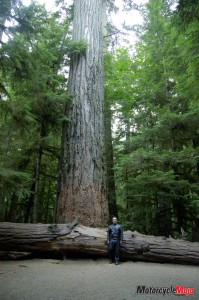

Half a million trees – some up to 76 metres in height and hundreds of years old – cover the entire park island, which is larger than New York City’s Central Park and contains 200 kilometres of walking, biking and driving trails. The city aquarium is here, as are the famous totem poles of various indigenous tribes, unique to northwestern B.C. and southern Alaska. Contrary to myth, the poles were not idols, nor were they worshipped, but rather, each was a coat of arms, the individual figures carrying specific meaning. The people also carved dugout canoes from the trunks of the tallest and widest trees, and there is evidence that one such ancient vessel actually made it to Hawaii, an adventure I can hardly imagine. The day was a serendipitous pause in a westward trip that would ultimately take me to the end of the Trans-Canada in Tofino before I turned back toward home. From prairies to peaks to Pacific and back, the journey left many high points indelibly etched in my travel memories, and instilled a heightened pride in, and gratitude for, my home and native land.