A DCT might feel like an automatic, but it offers the performance and responsiveness of a manual transmission.

The dual-clutch transmission (DCT) first appeared in race cars as a means to shorten the time lost while shifting gears, which ultimately dropped lap times. The technology then worked its way into high-performance sports cars, and today is used very sparsely in motorcycles, primarily on some Hondas. So what is a DCT?

A DCT essentially offers the ease of operation of an automatic transmission with the mechanical efficiency of a manual gearbox, though it resembles the latter much more closely. It does not experience any fluid losses as does a torque-converter automatic, nor is there the loss of power that is inherent in a continuously variable transmission due to belt friction. Like a manual gearbox, the DCT utilizes straight-cut cogs for each ratio, so there is a direct transfer of torque from the engine to the rear wheel. This is mechanically efficient, and it can handle high horsepower.

Where it differs from a manual gearbox is in the way it changes gears. On a manual transmission, gear changes are made entirely by the rider: the clutch and shifting mechanism must be actuated manually. Also, only the selected gear is engaged when in use; the other gears are meshed together, but they free-wheel. So, for example, when you shift from second gear to third, second gear is disengaged and third is engaged before the clutch is released.

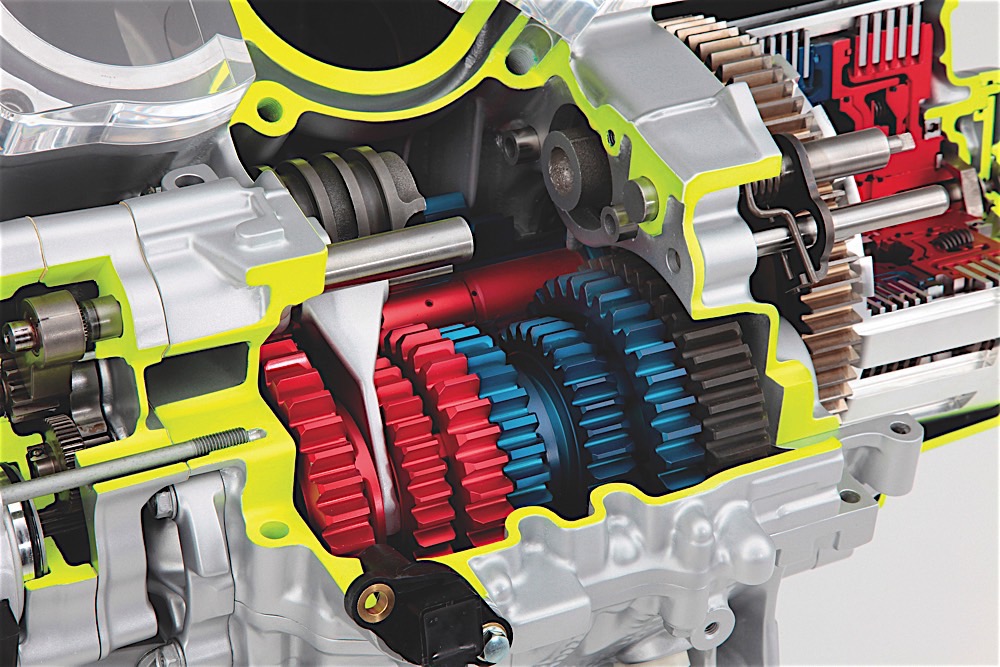

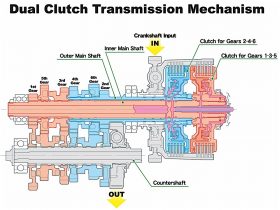

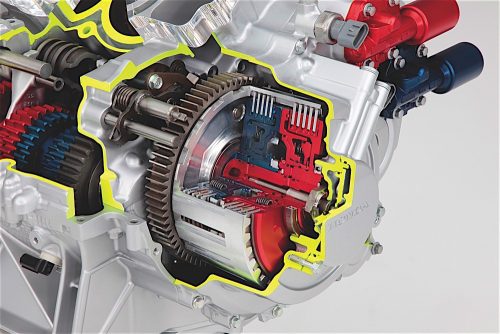

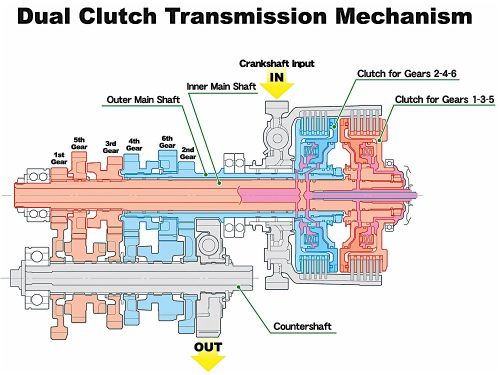

On a DCT, two gears are always engaged; the current gear being used, and the next gear up or down, depending on whether you are shifting up or down the ratios. However, to avoid the gearbox from exploding by meshing two different gear ratios, there are two separate clutches (housed in a single unit) that work independently from each other. They are both located on the mainshaft, which is actually a two-piece item with an inner and outer shaft. One clutch transfers power to the inner shaft, onto which gears 1, 3 and 5 are fixed, and the other clutch transfers power to the outer mainshaft, onto which gears 2, 4 and 6 are fixed.

Upon upshifting to second gear, for example, the inner mainshaft clutch disengages, releasing the engine’s torque from first gear, while the outer mainshaft clutch engages simultaneously, applying the torque to second gear, which is already engaged. In the meantime, the shifting mechanism disengages first gear and engages third gear, which spins freely because it is on the inner mainshaft, whose clutch is disengaged. The process is repeated when changing from second to third, third to fourth and so on.

Upon upshifting to second gear, for example, the inner mainshaft clutch disengages, releasing the engine’s torque from first gear, while the outer mainshaft clutch engages simultaneously, applying the torque to second gear, which is already engaged. In the meantime, the shifting mechanism disengages first gear and engages third gear, which spins freely because it is on the inner mainshaft, whose clutch is disengaged. The process is repeated when changing from second to third, third to fourth and so on.

Because operating two clutches simultaneously would be nearly impossible for a rider to perform manually, the clutches are operated hydraulically by computer-controlled solenoids. The shifting mechanism, too, is controlled electronically through a servomotor. Shift time therefore depends entirely on the clutches’ ability to work simultaneously, which is why the DCT gear changes are quick, and almost seamless. This system is very similar to what expensive, exotic cars have, often identified by the steering wheel-mounted paddle shifters.

This electronic shifting management also allows engineers to program almost any shifting map they want.

On DCT Hondas, you can choose between two automatic modes: D for fuel-efficiency and cruising comfort, or S for more aggressive riding. In these modes, gear changes are initiated automatically by the bike’s ECU based on preset parameters. If a rider prefers instead to choose when to change gears, selecting manual mode allows semi-automatic gear changes, usually via handlebar-mounted switches. The shifts are semi-automatic because, although it’s the rider who chooses when to shift gears, the shifting and clutch work are still handled by the bike. Regardless of which mode is selected, internally the gear-changing process is the same.

There is another type of auto-shifting manual gearbox, though it is not to be confused with a DCT. It is the automated manual transmission, and it was used exclusively in the Yamaha FJR1300A and, in the four-wheeled world, in cars like the diminutive Smart. This type of transmission is actually a manual gearbox, but instead of the clutch and shift mechanisms being operated manually by the rider, they are operated automatically by servos. Although technically such a system can be programmed to provide automatic gear changes, Yamaha chose to offer only manual shifting on the FJR, either by handlebar-mounted switches or by the foot shifter, which actually operated electric switches. The Smart car does offer automatic shifting. Either way, shifting on such a transmission is less refined, slower and sometimes awkward, especially when manoeuvring at low speeds.

The main downsides of a dual-clutch transmission are that it adds weight, complexity and cost to a machine. There are some peripheral benefits, however, especially for riders who have limited use of their left hand or left foot.