Although carburetors have been replaced by more efficient fuel injection on modern motorcycles, there are still plenty of older, carburetted bikes out there. Carburetors require some periodic adjustments, and one item that needs to be verified occasionally on multi-cylinder engines is carburetor synchronization. On bikes that have more than one cylinder, synchronizing the carburetors allows the cylinders to work in unison as the throttle is opened, thus allowing all cylinders to operate with the same output (some V-twins use only one carburetor, so this is unnecessary). The engine therefore operates smoothly and efficiently. Carburetted engines that are out of sync will vibrate, possibly lack power, and sound, well, off.

The ideal way to synchronize carburetors is by using a synchronizing tool, which plugs into the individual intake manifolds and measures intake manifold vacuum as the engine runs and the throttle is operated. The tool will display the vacuum level for each cylinder simultaneously, either on a set of gauges or in a series of fluid-filled transparent tubes. If the throttles are not set equally, the vacuum will not read evenly; the vacuum will be higher on the cylinder or cylinders on which the throttle valves are slightly closed, compared to the cylinders with lower vacuum readings. The more the throttle is closed for a given engine speed, the higher the intake vacuum will be.

The ideal way to synchronize carburetors is by using a synchronizing tool, which plugs into the individual intake manifolds and measures intake manifold vacuum as the engine runs and the throttle is operated. The tool will display the vacuum level for each cylinder simultaneously, either on a set of gauges or in a series of fluid-filled transparent tubes. If the throttles are not set equally, the vacuum will not read evenly; the vacuum will be higher on the cylinder or cylinders on which the throttle valves are slightly closed, compared to the cylinders with lower vacuum readings. The more the throttle is closed for a given engine speed, the higher the intake vacuum will be.

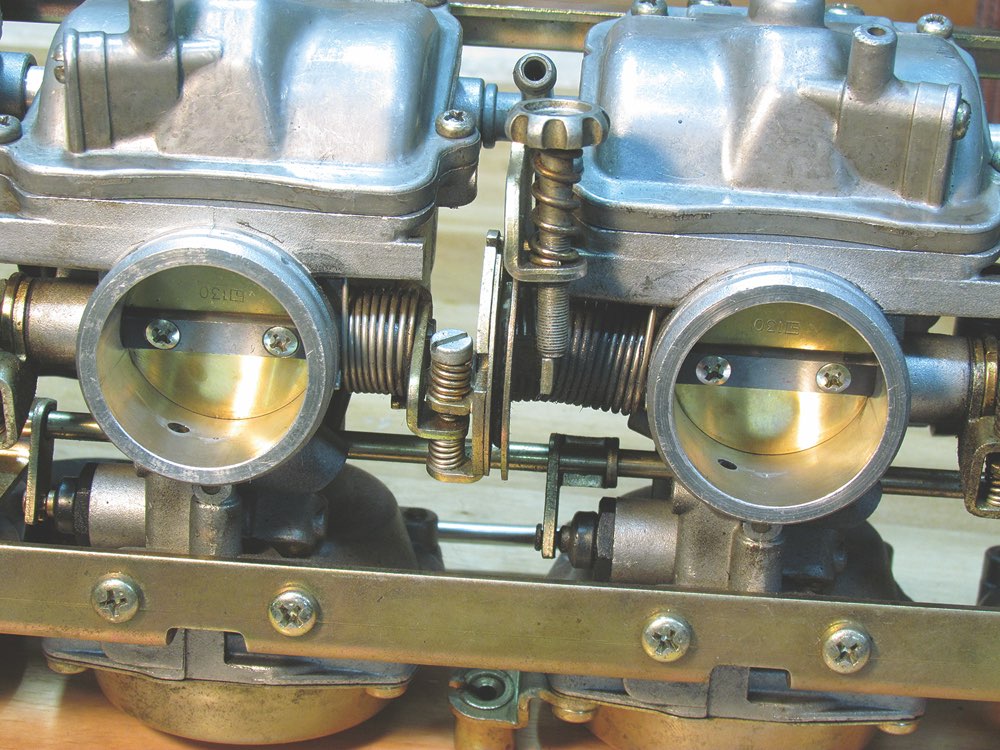

Adjusting the throttle valves varies depending on the carburetor configuration. If the individual carburetors are far apart, as on a boxer twin, the adjuster will be at the throttle cable going to each carb. Parallel-twins and inline-fours have individual carburetors lined up side by side, with screw-type adjusters connecting the throttle valves between adjoining carburetors. Some older slide carburetors have adjusters atop each slide.

If you don’t have a synchronizing tool, you can still synchronize carburetors accurately, though to do so, it’s best to remove the carburetors from the bike to allow access to the butterfly valves or mechanical slides from the rear. It’s important to note that you must use the butterfly valves on CV carburetors, since the vacuum slides don’t move unless the engine is running.

If you don’t have a synchronizing tool, you can still synchronize carburetors accurately, though to do so, it’s best to remove the carburetors from the bike to allow access to the butterfly valves or mechanical slides from the rear. It’s important to note that you must use the butterfly valves on CV carburetors, since the vacuum slides don’t move unless the engine is running.

On a twin, there will be one adjusting screw; on a four cylinder, there will be three. On a bank of four carburetors, each outer screw adjusts the throttle valves of the adjoining outer carburetors, and the centre screw adjusts the throttles of the left- and right-paired carburetors to each other.

To set the throttle valves equally, you can use a solid wire or a very small drill bit as a gauge to measure the gap between the throttle valve and the carburetor bore. The smaller the wire or drill bit, the more accurately you can adjust the throttle valves, since at small throttle openings it requires a very small adjustment at the screws to see a measureable difference, as opposed to when the throttles are opened wider. A wire or drill bit that measures less than 1 mm is ideal; I used a number 65 bit to adjust the FZ750 carbs pictured here.

On a four-cylinder engine, the carburetors can be adjusted in pairs. The best way to hold the throttle steady while synchronizing is to turn in the idle speed screw until you feel a slight drag on your measuring gauge at the throttle valve of the “base” carburetor. The base carburetor is the one connected directly to the throttle cable linkage, and on a four-cylinder engine, that’s usually cylinder number two. Note the number of turns of the idle screw from the starting point so that you can put it back after you’re done. You can further readjust the idle to spec once the engine is warmed after reassembly.

Begin by setting the gap at the base carb, which won’t change when the other carburetors are adjusted. Next, adjust the throttle gap at its adjoining carb (number 1) accordingly, using the adjusting screw. Move to carburetors 3 and 4, setting their throttle valves evenly, without, at this point, taking into account the adjustment of carburetors 2 and 3. Once you’ve adjusted carbs 3 and 4 evenly, you can use the centre adjusting screw to balance out the two outside pairs of carburetors. All you need to do at this point is to check the gap at carbs 2 and 3, since carbs 1 and 4 will follow their mating carburetors.

Done carefully, the carburetors will need no further synchronization once back on the bike. However, this does not mean you’ll get even vacuum at the intake manifolds should you verify it. If the engine is in excellent condition, the vacuum readings should be spot on. However, if the vacuum readings are uneven, this indicates that the cylinders with low intake vacuum are low on compression, which means there’s likely more work to do down the road.

Technical articles are written purely as reference only and your motorcycle may require different procedures. You should be mechanically inclined to carry out your own maintenance and we recommend you contact your mechanic prior to performing any type of work on your bike.